Jeffrey Kegler's blog about Marpa, his new parsing algorithm, and other topics of interest

Marpa resources

The Ocean of Awareness blog: home page, chronological index, and annotated index.

Jeffrey Kegler's blog about Marpa, his new parsing algorithm, and other topics of interest

The Ocean of Awareness blog: home page, chronological index, and annotated index.

I'm converting Marpa to XS and have started to use Cweb. Cweb is the C version of the "literate programming" system pioneered by Don Knuth. I'm pleasantly surprised by it. Cweb adds fun to the programming experience and is helping in more ways than the phrase "literate programming" would suggest.

One very important feature of Cweb

is something that would seem to be a nuisance,

or at best an implementation detail.

The

Moving one step back from the "translation unit" separates the presentation of the code from the issues of linkage and scope. Over the years, I'd gotten used to organizing my code around the visibility rules for the compiler and the linker. With Cweb, I can lay out C code in the same way that I think about it. It surprises me how liberating this is.

Suppose we are adding an element to a C structure. Typically required might be:

Here is some C logic which, while very small, nonetheless has 6 of the 7

components listed above.

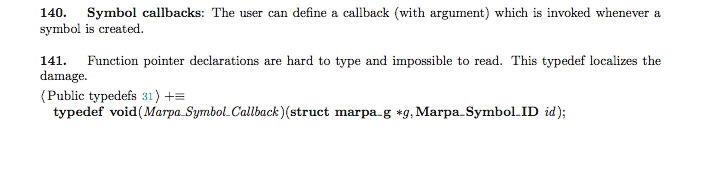

In Cweb I was able to put them all together. Here's the bottom of one page of my "woven" Cweb code:

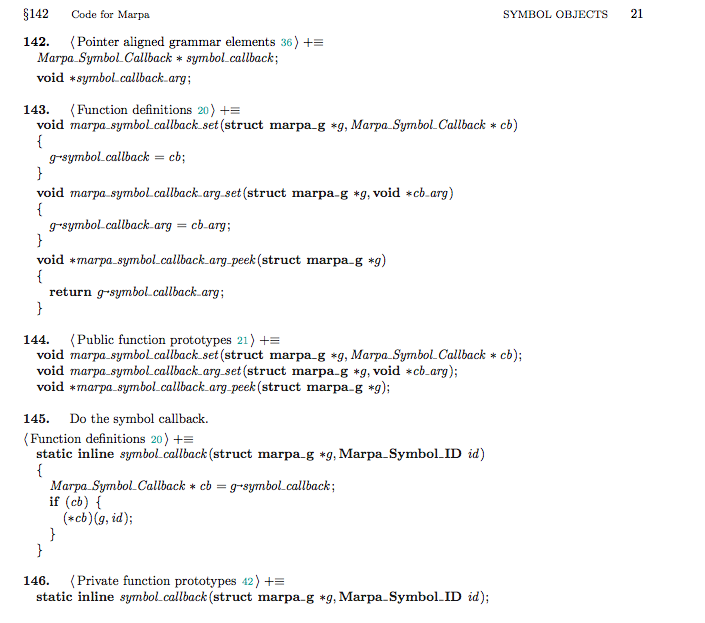

... and here is the top of the next:

For some readers, these samples may adequately illustrate my point. For those curious about the code, I'll close with a few explanations. The code, as I said, is for the XS version of Marpa. For those not familiar, Marpa is a general BNF parser generator -- it parses from any grammar that you can write in BNF. If the grammar is of any of the kinds currently in practical use (yacc, LR(k), LALR, LL, recursive descent, etc.), this parsing is in linear time.

Marpa uses Perl callbacks, and so the XS version must be able to call back to Perl closures. So where is all the Perl logic in my example?

For the XS conversion, I'm separating the code into three layers:

I am only using Cweb for libmarpa. (Cweb only understands C language.)

Since libmarpa has no Perl-specific logic, its role in dealing with Perl callbacks is very simple. libmarpa needs code to store the callback (which from its point of view is just a C function pointer), and some other code to perform the callback. C does not have closures, so to implement a poor man's version of these, the callback is allowed an argment, which can be examined and set. It comes out to a couple of dozen lines of code, the majority of which are declarations and data definitions.

One thing is missing from the example -- "destructor" logic.

The pointers in the example do not "own" the things that they point to,

so there is no need to deallocate anything.

When allocation and deallocation are separate, it is easy to forget

whether you omitted deallocation logic because it was unnecessary,

or because you forgot.

Using Cweb, I always put allocation and deallocation together.

Perhaps that's not enough to make memory leaks a thing of the past,

but it certainly makes life easier.

posted at: 19:40 | direct link to this entry